Brief History of Wild Wolves

Few wild animals have captivated the human imagination like the wolf (Canis lupus), considered to be North America’s dominant carnivore. Other than the great apes, there are few animals that are as similar to humans in terms of their social organization and family structure. The indigenous peoples of the Americas understood this, frequently depicting the wolf in their art and oral histories. Their paintings and stories often displayed wolf and human joined as one powerful creature. In some legends, the wolf is given healing powers, and in others, the wolf saves people from a great flood. Ray Pierotti and Brandy R. Fogg detail how The Blackfoot, Lakota and Cheyenne claim to have learned to hunt from wolves, and believed that “wolves live lives that parallel those of humans, and thus represent another people that must be respected.”

For thousands of years, humans and wolves coexisted in this manner. As biologist L. David Mech has observed, there was a time when, excluding our own species, the wolf was the most widely distributed land mammal in the world. Although we cannot say with certainty, there were at least 250,000, and perhaps as many as two million, wolves inhabiting what would become the continental United States. This relationship drastically changed as European colonization began.

The Destruction of the Wolf

There are many social, cultural and economic factors that cast the wolf as the enemy in the European colonists’ eyes. Practically speaking, Europeans had more established agrarian townships and settlements. The livestock, such as cattle and sheep, that they depended on for food and other resources were threatened by the overwhelming presence of wolves and other predators in the “new world.” In contrast to the lore and mythology of Native Americans, the wolf was almost categorically represented as a ravening, bloodthirsty killer in the Christian tradition and in Western culture as a whole. The wolf became a symbol of the untamed and the unknown, and of a violent and rapacious wilderness. It elicited connotations of the demonic and satanic in the European psyche. The hunting of wolves in America far predates the founding of the U.S. The first documented wolf bounty was instituted in the colony of Massachusetts in 1630; this signaled the beginning of a 350-year-long campaign to wipe wolves off the continent.

Photo courtesy of NPS/Jim Peaco

With the advent of industrial technology and the livestock industry, certain societies began waging a war against the wolf that at times seemed to span the globe. The U.S. government was the most zealous in its persecution of the predator, implementing a nationwide policy of wolf control. Wolves were seen as evil killers that posed a threat to the continued safety and prosperity of the American people, a view that settlers frequently applied to Native Americans as well. President Theodore Roosevelt, a man who is generally renowned for his environmental activism, declared the wolf “the beast of waste and desolation” and called for its complete eradication. Wolves were shot, trapped, poisoned, tortured, and burned alive. Wolf skulls and pelts were piled high for victory photographs and to claim the lucrative bounties. Many hunters (often called “wolfers”) believed they served God and country by clearing the countryside of such vermin. Along with the buffalo, the wolf was deliberately driven to the brink of extinction by humans. As environmental historian Brett Walker recounts, the U.S. was so proud of its prowess in killing wolves that it sent representatives to other industrialized nations like Japan to help them destroy their wild wolf populations as well.

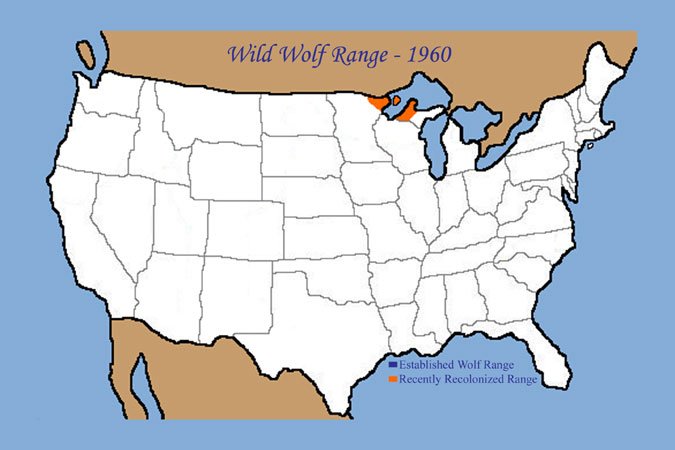

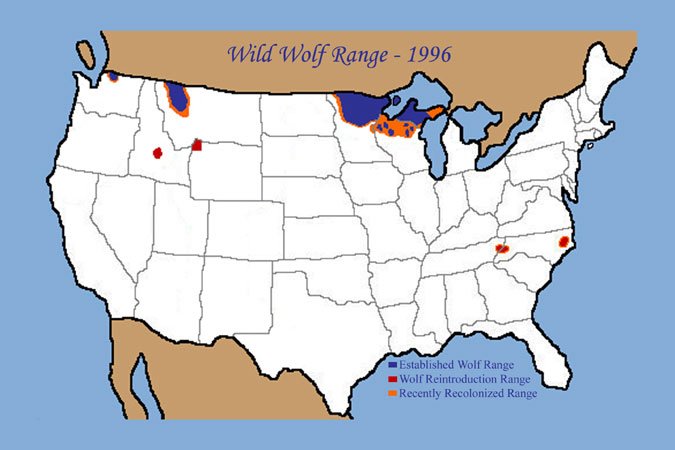

Through the systematic extermination of every wolf to be found, the U.S. appeared to have won its war against wild nature. Over the course of a few centuries, the wolf population was reduced from the millions to the hundreds, with the last few survivors in the lower 48 states retreating deep into the woods of present-day Michigan and Minnesota for safety.

The fanaticism and scope of the crusade against wolves by the U.S. cannot be overstated. Naturalist writer Barry Lopez asserts that Americans persecuted wolves almost pathologically, and that, “wolf killing goes much beyond predator control…the history of killing wolves shows far less restraint and far more perversity.”

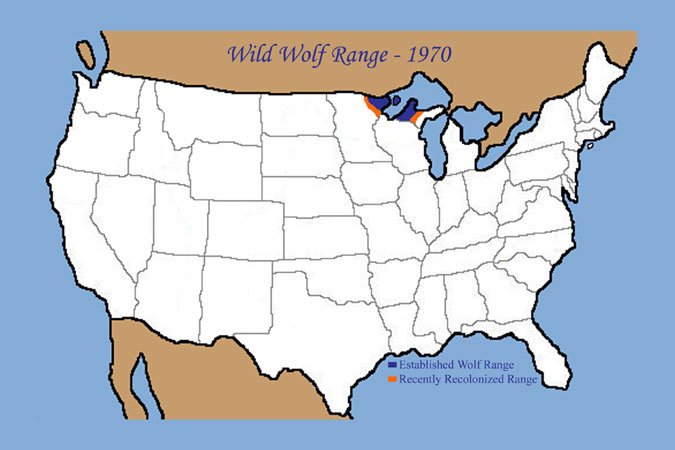

Keeping this dark history in perspective, it is truly miraculous that there are any wolves left in the U.S. at all. To be clear, the federal government incentivized the killing of wolves as late as 1965, and many hunters still combed the Great Lakes region for the elusive packs that had taken refuge there. Despite their best efforts, the northern timber wolves held their ground and actually began to make a slight comeback. With the cover of a vast, dense forest, and the recolonization of dispersing wolves from Canada, Michigan and Wisconsin’s wolves persevered. By 1970, there were a few reports of wolf sightings farther from the Canadian border than there had been in over a decade. The last of America’s wild wolves were starting to win more public interest and concern, and talk of endangered species conservation and legislation had just begun in the environmentalist movement.

The Protection of the Wolf

Wolf pups in Yellowstone, photo courtesy of NPS

It was only after the monumental declaration that the gray wolf would be federally protected under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1974 that widespread wolf recovery truly became possible. The public’s interest and fascination grew in leaps and bounds as modern Americans became further removed from nature. As so often is the case, it was only after wolves had vanished that we began to value what we had lost.

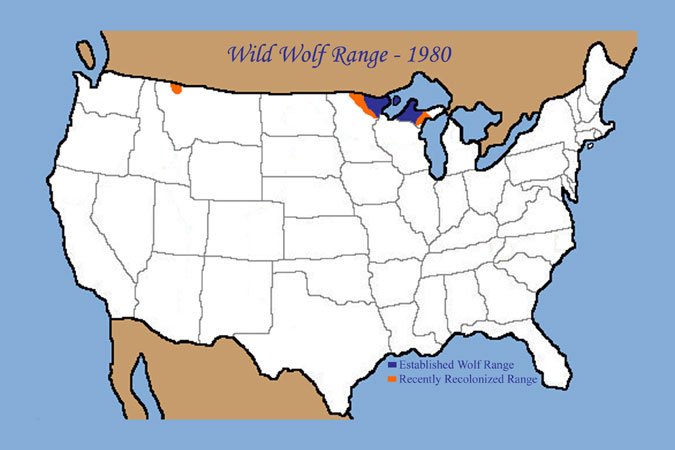

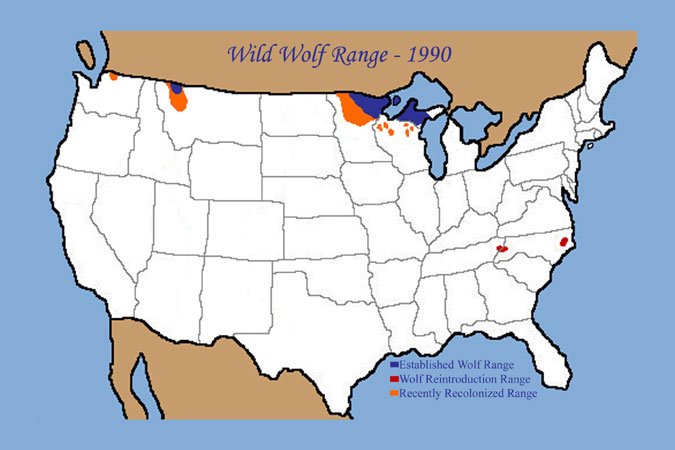

The northern gray wolf took a huge step on the road to recovery when the first pack of wild wolves crossed the border from Canada to Glacier National Park, Montana. Wolf conservationists and advocates, in their joy and disbelief, dubbed them the Magic Pack. Meanwhile, the Great Lakes population grew steadily, spreading into northern Wisconsin. By 1990, Montana’s Magic Pack had company, as other packs continued to migrate from Canada, and the first wolves were born on Glacier National Park soil. The first substantial reports of wolf sightings in the Cascade Mountains of Washington State came in, and the U.S. could now boast a possible population of wolves in seven states, including Alaska.

The Mexican Gray Wolf

As the northern gray wolf made great strides toward reestablishing itself, its smaller cousin, the Mexican gray wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) faced oblivion. Smaller than the typical gray wolf, the Mexican gray is usually sandy or tawny colored, and lives in smaller packs better adapted to high desert environments. This species had already been extinct in the American Southwest by 1970s, and the last few in Mexico were under serious attack. The year 1980 marked its complete extinction in the wild. However, due to pressure from the ESA, the last seven wild individuals were captured and placed in a captive-breeding program. By using a breeding registry, biologists hoped to preserve the genetic diversity of the animal and save this unique subspecies.

The Red Wolf

In the American Southeast, the red wolf (Canis rufus) was also faced with dire prospects for survival. The red wolf is a completely different species from the gray wolf, and the only distinctly American wolf. It is smaller, with reddish and brown coloration, and almost has the appearance of a wolf-coyote cross. Prior to colonization, the red wolf lived across the East Coast and Southeastern seaboard. However, like the gray, the red wolf was hunted to extinction throughout its range. By 1980, red wolves survived only in captivity, their breeding highly regulated in order to preserve precious genetic diversity.

Yellowstone and Other Reintroduction Programs

Eager onlookers watch as wolves are transported to Yellowstone. Photo courtesy of NPS/Diane Papineau

The watershed moment in wolf policy and recovery over the past century was undoubtedly the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park and Idaho in 1995. After years of political debates and grassroots efforts, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service brought 31 wild gray wolves from Canada to Yellowstone and the Frank Church Wilderness of Idaho.

The reintroduced wolves in Idaho were “hard released” directly into their potential habitat from their transportation crates. One female wolf traveled over 60 miles in the first day looking for her Canadian homeland. In cooperation with the U.S. government, the Nez Perce Nation took over the reintroduction effort of wolves that roamed into their tribal lands.

To prevent this reaction, the first wolves to inhabit Yellowstone were reintroduced more gradually. They spent three months in acclimation pens in the back country, until the dominant male of what would come to be known as the Crystal Creek pack mustered up the courage to take his first steps out of the pen and into a new era for wolves. Despite the disappointment of some wolves being illegally poached as they roamed around the fringes of the park, biologists were overjoyed as packs established territories and gave birth to the first litter of pups to be born in Yellowstone in nearly 70 years.

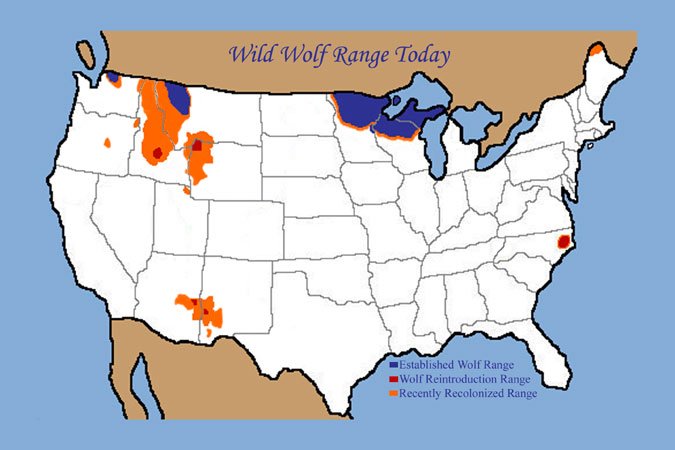

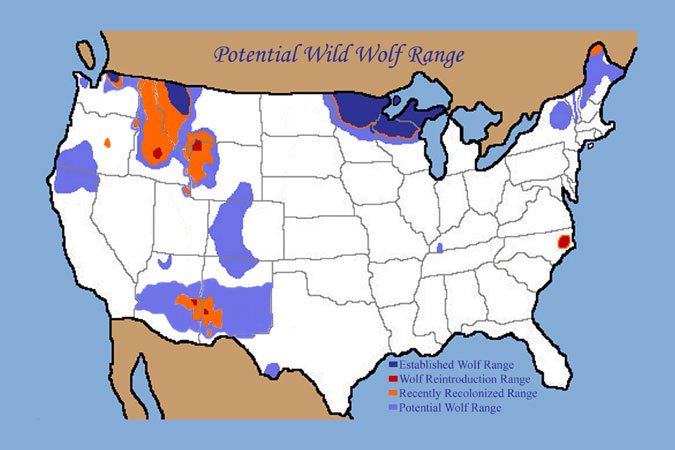

Over the past four decades or so, the wild wolf population in the contiguous U.S. has grown from less than 300 to approximately 5,600. Even in the 1990s, it looked like wolves would eventually disappear entirely from the plains, forests and mountains of America. Yet, as people searched ever more desperately for a true connection to nature and realized the terrible consequences of the war against wildlife, we slowly and painfully learned the value of balanced ecosystems and the animals that inhabit them. In the years since the Yellowstone reintroduction, astounding research has been conducted on the park’s wolves and the vital role they have as a apex predators. We have learned that they catalyze an ecological phenomenon known as a “trophic cascade.” As ecologists Christine Angelini and Brian Silliman concisely put, this term refers to a predator’s impact “trickling down one or more feeding levels to affect the density or behavior of the prey’s prey.” Wolves have started such a cascade in Yellowstone by hunting elk and deer and changing their grazing patterns. In the absence of wolves, they had been decimating the park’s grasses and sapling trees, which caused massive erosion and deprived many other species of their habitats. Since the return of wolves, the grasses and trees have rejuvenated, and biodiversity has increased.

Wolves are coursing predators, meaning that they make their prey run. Photo courtesy of NPS

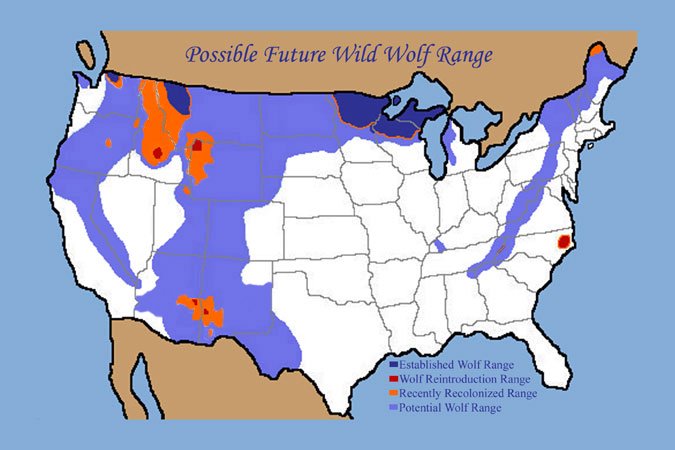

Yellowstone is a unique case, but similar effects have been noted elsewhere. All this is to say that the wolf has an extremely important function in maintaining healthy environments, and is a creature to be respected, not feared. Gray wolves now inhabit 13 different states, with California being the most recently recolonized. Since the passage of the ESA, the wolf’s endangered species status has continued to fluctuate at both the federal and state levels. These decisions have often been driven by politics rather than science. In late 2020, gray wolves once again lost federal endangered species status, and their management was returned to individual states. Despite this, their numbers are slowly stabilizing.

Inspired by the success of Yellowstone, the Mexican gray wolf was reintroduced in Arizona in 1998. As of 2019, over 150 wild Mexican grays inhabited the lands on the border of Arizona and New Mexico in 42 different packs, with a few having roamed south back into Mexico as well. The Mexican gray population has benefitted from innovative conservation strategies such as introducing captive-born puppies into wild litters, which the mothers often readily accept. Hopefully this success will continue, although reintroduction efforts continue to be hampered by extremely partisan politics.

The state of the red wolf, now the most critically endangered wild canid in the world, is unfortunately much more precarious. In 1990, the first red wolves were reintroduced to the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in North Carolina. For a time, the program was quite successful, with the population peaking at more than 100 in 2012. But due to lack of public support and public lands, human intolerance and political infighting, that number plummeted to less than 50 by 2018. Red wolves are under constant threat of being de-listed from the ESA by political lobbies who claim that it is a mongrel wolf-coyote hybrid rather than a distinct species. De-listing would almost certainly be a death sentence for red wolves. As of October 2020, there were only seven radio-collared wild red wolves known to exist in North Carolina.

Wolves Today

While the future of some wild canids like the red wolf is grim, there is heartening news from around the world for wolves. Populations in Canada remain strong and largely consistent, despite being hunted by humans. Overseas, the European gray wolf has slowly made a comeback in Italy, Switzerland, France, Poland, and even Scandinavia. The endangered but resilient Iberian wolf has also greatly benefited from conservation efforts and reintroduction programs in Portugal and Spain.

Back in the U.S., History was made in Colorado in 2020 when the state’s citizens voted to approve Proposition 114, which mandates that Colorado Parks and Wildlife will reintroduce wolves to the state by December 31st, 2023. This was an unprecedented ballot measure, as all other wolf introductions had been federally managed through the ESA. Although in recent years there have been several sightings of wolves who have ranged south from Wyoming, there hasn’t been any firm data on how many may be residing within the state’s borders, if any.

A wild wolf in Lamar Valley. Photo courtesy NPS/Jim Peaco

The recovery of wolves is no longer a distant dream, but there is still much work ahead. Despite a growing body of scientific research that clearly shows wolves are not a threat to humans or the livestock industry, excessive wolf culling still occurs frequently across the country. Wild wolves are often hunted and killed for allegedly killing cattle and sheep. There are documented incidents of this, which should be properly addressed by local authorities — but the reality is that wolves account for a startlingly small amount of livestock death. Mountain lions, bears, coyotes, and even our domestic dogs kill livestock at much higher rates than wolves do. Many studies have concluded that killing wolves actually causes more livestock death, and that non-lethal management techniques are generally far more effective than lethal ones.

Although we will almost certainly never see wild wolves in their historic numbers, they have made a remarkable comeback over the past 50 years. If recovery efforts continue, we may one day see wild wolves coexisting with humans in over 20 states. With the wolf’s return, we are relearning that it is possible to live in close contact with wild wolves and other large carnivores. With collaboration from politicians, environmentalists, and ranchers, we may not be forced to choose between people, wildlife, and livestock. The wild habitat that is currently left across the nation could easily support all three. How we choose to value America’s natural heritage, and wildness as a whole, will determine whether this becomes a reality. There are still great challenges ahead, but we remain confident and hopeful that wolves and humans can once again live in harmony across all of North America, and the world.

By Austin Hoffman and Annie White. Graphics provide by Annie White, Mission: Wolf archives, and the National Park Service. Updated in 2021.

References

The First Domestication: How Wolves and Humans Coevolved Raymond Pierotti & Brandy R. Fogg (2017)

The Lost Wolves of Japan, Brett L. Walker (2005)

Vicious: Wolves and Men in America, Jon T. Coleman (2004)

Website Links:

National Park Service

Red Wolf Project

“Introduction to The Red Wolf”

Defenders of Wildlife

Colorado Parks & Wildlife

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service:

“Gray Wolf Biologue”

“About Red Wolves”

National Park Service:

“Yellowstone Science: Issue number 24-1: Celebrating 20 Years of Wolves”

International Wolf Center:

“Wolves of the World”

The Wolf Almanac, Robert H. Busch (1995)

Decade of the Wolf, Gary Ferguson and Douglas Smith (2005)

Of Wolves and Men, Barry Lopez (1978)

Wolves: Behavior, Conservation and Ecology, David L. Mech and Boitani Luigi (2003)

Wolf Nation, Brenda Peterson (2017)

Predatory Bureaucracy, Michael Robinson (2005)